Why You Should Not Strength Train in 2026

A deep dive into the research on strength training, performance and injury risk - and why added gym work may distract from what actually improves race results.

There is no physiological reason why a long run should occur every seven days yet, most runners structure their training this way because their work and social life tend to operate on a seven-day rhythm. This predictability makes planning simpler and training adherence and execution easier.

The same logic applies to the New Year. There is no biological reason to start a new habit on the 1st of January yet, the turn of the year is widely framed as a reset - a clean break where past mistakes are left behind and better behaviours begin. The New Year’s resolution is less about physiology and more about narrative, structure and social reinforcement.

For runners, that resolution is often strength training. You have likely read countless articles and listened to just as many podcasts claiming that strength training will make you faster, more resilient and less injury-prone. The message is consistent enough that it has become almost self-evident: if strength training improves performance, then committing to it, especially as a structured, time-bound resolution, should logically lead to better running.

But does it? And more importantly, even if strength training does work, is it the best thing to focus on during the year ahead?

Evaluating the Evidence for Strength Training

At Born on the Trail, we do not take commonly repeated claims at face value. As the famous quote goes, “Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence,” so that is what we will do. First, we need to establish whether strength training delivers the performance and injury-related benefits that are so often attributed to it and secondly, we need to understand if this intervention should be your focus in 2026.

Performance Effects of Strength Training

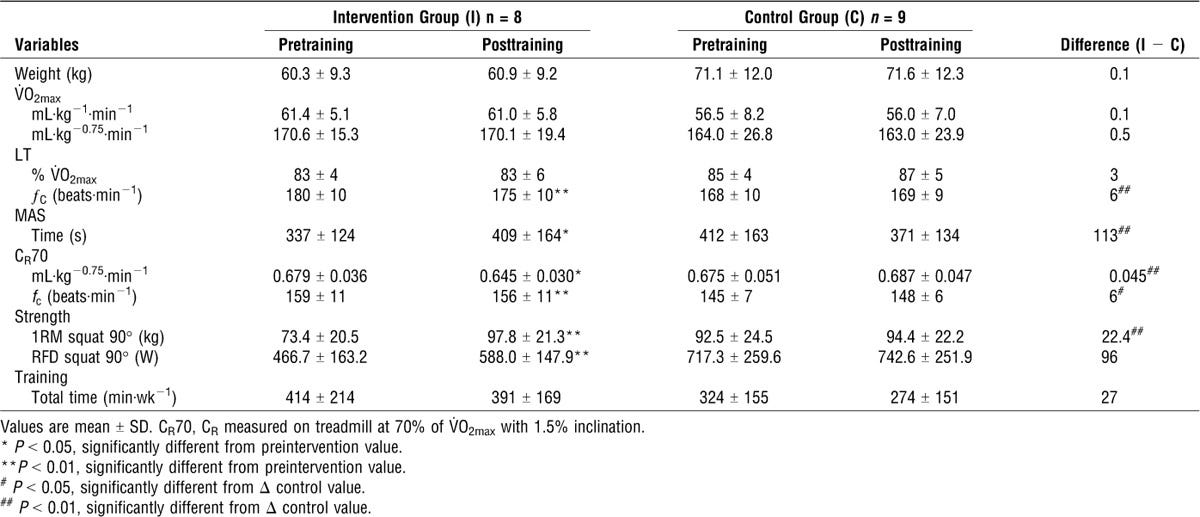

One of the most frequently cited studies in this area dates back to 2008 [1] (which is 18 years ago now…) In this trial, well-trained runners (average age 29, with an average 5 km time of roughly 19 minutes) were divided into an intervention group and a control group. The intervention group supplemented their usual endurance training with half-squat strength training, four sets of four repetitions maximum, three times per week, for eight weeks. The control group continued with their normal endurance training only.

After eight weeks, the intervention group demonstrated a 5% improvement in running economy at 70% of VO2max, a 21.3% increase in time to exhaustion at maximal aerobic speed, a 2.8% reduction in heart rate at lactate threshold and a 1.9% reduction in heart rate at 70% of VO2max. The control group showed no such improvements. Importantly, the intervention group exhibited no changes in body weight, VO2max or other physiological metrics.

A similar pattern was observed in another study [2] involving 20 middle-distance runners (1,500 m to 10,000 m) with an average VO2max of 61. Participants were split into an intervention group, which added a structured 40-week strength training programme on top of their run training, and a control group that continued their existing training routines. After 40 weeks, the intervention group improved running economy by 3.5% and velocity at VO2max by 4%. The control group showed smaller improvements, 2.3% in running economy and 1.9% in velocity at VO2max, though these changes were not statistically significant. As in the earlier study, no significant changes in body composition were observed within or between groups.

More recently, a 2025 study [3] reported comparable findings. In this trial, a ten-week strength and plyometric intervention was added to normal endurance training. Running economy improved by 2.1%, while time to exhaustion increased by 35% during a protocol consisting of a 90-minute run at 10% between lactate thresholds 1 and 2, followed by a time-to-exhaustion test. Over the same period, the control group experienced a 0.6% decline in running economy and an 8% reduction in time to exhaustion.

These individual findings are supported by a 2017 systematic review [4] analysing 24 published studies. The review found that running economy generally improved by 2-8% in middle- to long-distance runners following strength training, although not consistently across all studies. Time-trial performance over distances ranging from 1.5 to 10 km and anaerobic speed-related qualities also tended to improve. In contrast, variables such as VO2max, velocity at VO2max, blood lactate measures and body composition were typically unaffected.

Taken together, this body of evidence supports the conclusion that high-intensity strength training, when added to endurance training, can improve running economy and certain performance-related outcomes. This position is now broadly accepted within both the scientific literature and applied coaching practice, leading to generalised recommendations such as those summarised in the infographic below.

However, while the performance-related benefits of strength training are relatively well supported, the claim that it reduces injury risk is far less clear and warrants closer examination.

Strength Training and Injury Risk

One study [6] examined injury rates in novice runners (less than two years of running experience) assigned to one of three groups: a functional strength training group (including exercises such as lunges and squats), a resistance training group using elastic bands, and a stretching-based control group combining static and dynamic stretches. One of the most notable findings was that injury rates were similar across all groups, ranging from 26.7 to 32.9 injuries per 1,000 hours of running, which in itself is a relatively high injury rate. Injury incidence was also higher during the first eight weeks of the intervention compared with the subsequent four-month maintenance period, suggesting that the introduction of a new training stimulus may itself temporarily increase injury risk.

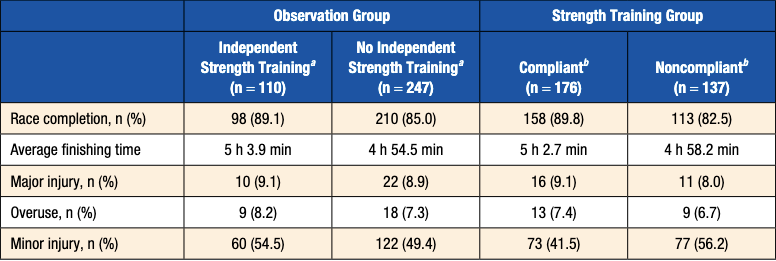

Toresdahl et al. [7] investigated the effects of strength training in a much larger cohort of marathon runners. In this study, 720 participants, with an average marathon finishing time of approximately five hours, were divided into a strength training group (352 runners) and a running-only group (368 runners). The strength group received instructions and a prescription for core, hip abductor and quadriceps strengthening exercises. The intervention did not result in a statistically significant reduction in overuse injuries leading to marathon non-completion, nor did it produce faster finishing times. Small reductions in minor injury incidence, average pain during the race and medical tent usage were observed, but none reached statistical significance.

Observational data further complicate the picture. Stenerson et al. [8] analysed 616 eligible responses from an online survey exploring relationships between resistance training habits and running-related injury prevalence. Although 44.6% of respondents reported sustaining a running-related injury in the previous year, no associations were found between resistance training participation and injury prevalence, either overall or when stratified by sex, age or running distance.

Finally, a comprehensive review by Šuc et al. [9] evaluated the broader evidence base examining whether resistance exercise reduces running-related injury risk. While some studies suggested a potential protective effect, others showed no benefit. The authors concluded that the evidence remains inconclusive, noting frequent methodological limitations, small sample sizes and an over-reliance on military populations - all factors that limit the generalisability of the findings to recreational and competitive runners.

Why the Conclusions Are Less Clear Than They Appear

Taken at face value, the body of evidence presented above appears relatively consistent: strength and resistance training can improve performance-related outcomes, most notably running economy, while its effect on injury prevalence is, at best, uncertain and inconsistent.

That conclusion would be reasonable if we stopped there however, I have a fundamental problem with much of the research underpinning these claims, particularly the studies reporting improvements in running economy.

In most cases, and in all the cases outlined above, strength training was added on top of an athlete’s existing endurance training. If the control group was running, for example, 50 km per week, the intervention group was also running 50 km per week plus two to three strength sessions. This is not a like-for-like comparison. The observed improvements may simply reflect a higher overall training load or the well-documented “new intervention” effect, rather than a specific benefit of strength training itself. If we want to understand whether strength training offers unique performance advantages, we need to examine studies where training volume is reallocated rather than increased.

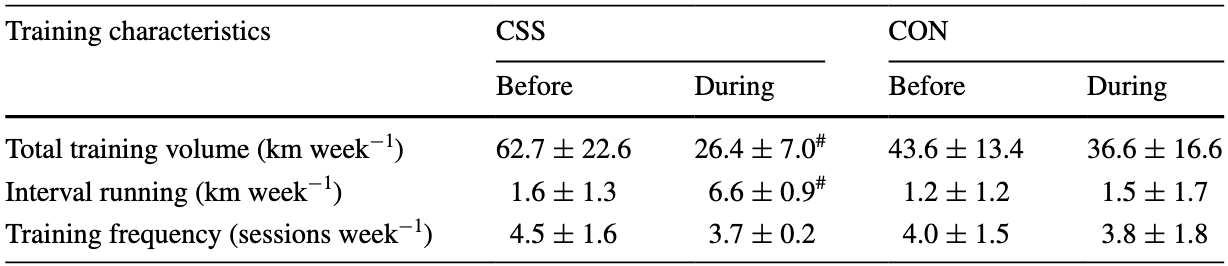

Vorup et al. [10] attempted to address this by dividing 16 male endurance runners (average VO2max of 60) into a strength group and a control group over an eight-week intervention. The strength group reduced their running mileage by 58% while incorporating two weekly strength sessions. Results showed a 4.8% improvement in 400 m performance and an 18.5% improvement in a Yo-Yo interval test consisting of 2x20-second sprints at progressively increasing speeds.

However, a closer inspection of the training data reveals important caveats. Although total mileage decreased substantially in the strength group, their interval-running mileage increased by more than 312%. Meanwhile, the control group also reduced their total mileage by approximately 16%, but increased interval running by only 25%. Unsurprisingly, short-distance performance improved, while 10 km performance remained virtually unchanged in both groups. My opinion is that the adaptations observed were far more reflective of increased high-intensity running exposure than of strength training.

A similar pattern appears in a study by a Finnish research group [11] investigating young distance runners aged 16-18 years. In this intervention, 19% of endurance training was replaced with explosive exercises, including running sprints and various jumping drills, with more than 95% of the remaining endurance training being performed below the anaerobic threshold. A 1.1% improvement was observed in 30-metre sprint speed which is once again testament to the fact that the strength intervention (sprints and jumps) was very specific to the testing protocol (a 30m sprint test). In contrast, maximal endurance performance, VO2max and running economy remained unchanged, showcasing how the intervention did not enhance long-distance efficiency.

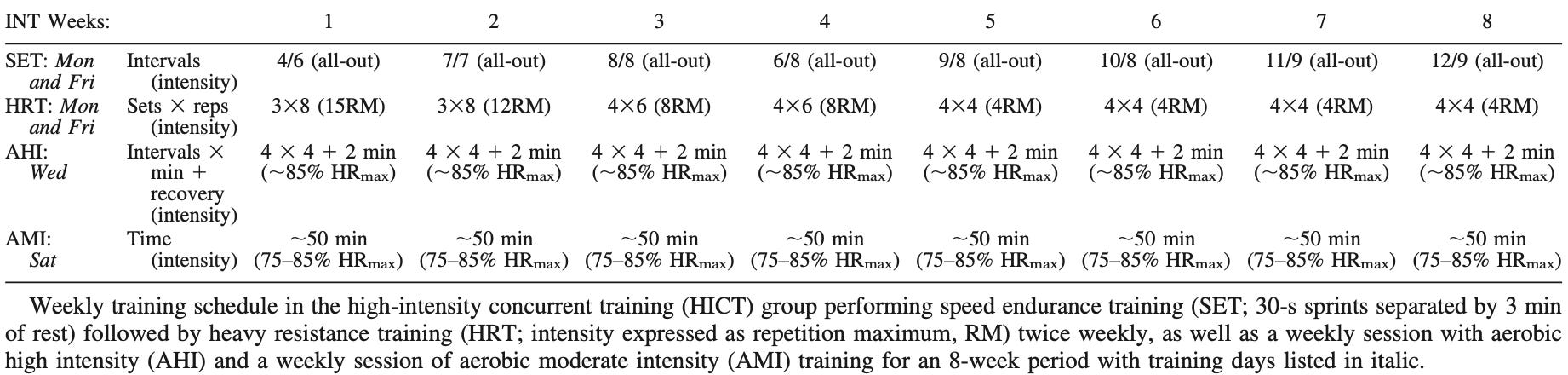

Skovgaard et al. [12] replaced 42% of weekly training volume, reducing running from 31 km per week to 18 km per week, with two strength training sessions. These sessions began with a warm-up, followed by four to twelve 30-second all-out running sprints, and concluded with heavy strength exercises focusing on the squat, deadlift and leg press. Strength training progressed from three sets of eight repetitions at manageable intensity to four sets of four repetitions at maximum intensity. Running training consisted of 4 × 4-minute intervals at heart rate zones 4 to 5 and a steady-state run of 40-70 minutes at heart rate zones 1 to 3.

The control group maintained habitual training of approximately 40 km per week, including interval running, though this decreased slightly from around 6 km per week to 4-5 km per week during the intervention period. Performance improvements favoured the intervention group, with a 44% improvement in the Yo-Yo test, a 5.5% improvement in 1,500 m time and a 3.8% improvement in 10 km performance.

Once again, however, the lack of uniformity between groups complicates interpretation. Despite a lower overall mileage, the intervention group accumulated substantially more high-intensity work through sprinting, interval training and heavy resistance exercise while the control group reduced their exposure to intensity. It is therefore difficult to attribute performance improvements, particularly over fast distances like 1,500 m or 10 km, to strength training itself rather than to a higher proportion of intense, race-relevant stimuli.

One of the more robust attempts to control for intensity distribution was conducted by Paavolainen et al. [13]. In this study, 32% of total training time in well-trained runners (average VO2max of approximately 64) was replaced with explosive-strength training in the intervention group, compared with just 3% in the control group. Importantly, both groups maintained identical intensity distributions, with 84% of training performed below lactate threshold and the remainder above it. The explosive sessions, lasting between 15 and 90 minutes, consisted of short sprints (5-10 × 20-100 m) and various jumping exercises, performed either without external load or with light barbell loads (0-40% of one-repetition maximum) at maximal movement velocity.

Following the intervention, the strength group improved their running economy by 8.1% and their 5 km performance by 3.1%, while the control group showed no improvement. While this does indicate a performance benefit, it is notable that the intervention relied heavily on sprinting and plyometric drills rather than the heavy, low-repetition resistance training protocols commonly cited as drivers of improved running economy.

Taken together, these findings suggest that performance improvements are largely driven by the specificity and relevance of the added training stimulus relative to the performance test, rather than by any inherent or generic benefit of strength training itself. When the stress from strength training closely resembles running, the intervention tends to result in improved performance, but when it does not, its benefits becomes far less clear.

The Highest-Return Training Intervention

Before going any further, it is worth returning to the beginning of the article. The turn of the year is often accompanied by renewed motivation and a desire to improve on the previous season. That motivation is, in itself, a positive thing, but care needs to be taken that the additional work and focus put into training generate the expected results. My argument is not that runners should avoid strength training per se, but that effort should be directed towards the interventions with the highest return before worrying about refinements such as strength training.

This naturally raises the question: what actually are the highest return interventions?

What Predicts Ultramarathon Success

Beat Knechtle and his team published a significant amount of studies looking to understand the determinants for performance in multiple ultra marathon races, and upon a closer look, the picture becomes very clear.

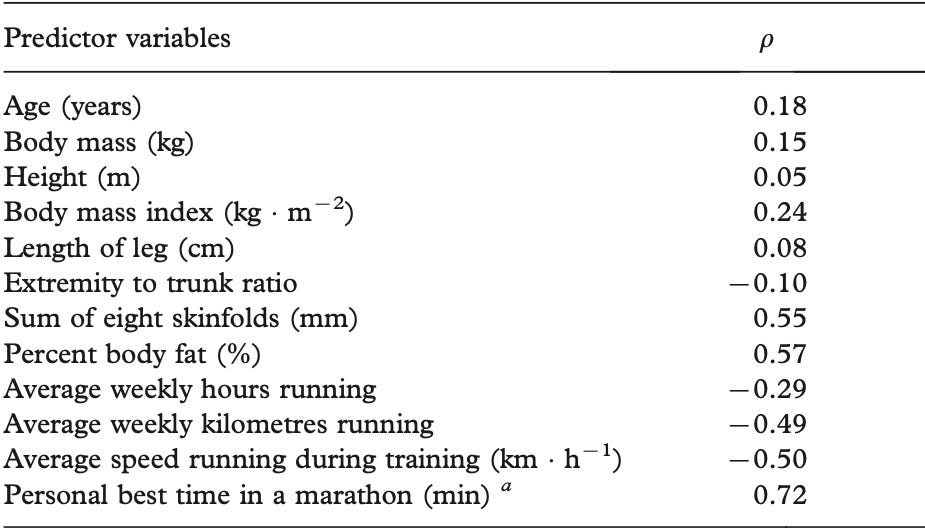

In a multivariate analysis (how multiple individual variables contribute to one singular metric) of 93 male runners competing in a 100 km ultramarathon [14], weekly training volume measured in kilometres emerged as the strongest predictor of performance. When examined using bivariate analysis (association between two singular variables), personal best marathon time was the single strongest predictor of ultramarathon race outcome.

In a separate multivariate analysis of 169 male runners competing in a 100-km ultramarathon [15], researchers further explored the interrelationship between training, experience and anthropometry (proportions of the human body). In the bivariate analysis, a previous personal best 100-km time emerged as the single strongest predictor of race performance, followed by marathon personal bests and average training speed. When these variables were examined through multiple regression models, training speed, weekly running volume, and age were identified as the most influential predictors of success. Notably, while anthropometric attributes were significantly associated with race outcomes in the bivariate analysis, they lost their predictive significance in the multivariate models once training and age were taken into account. These findings suggest that for a 100-km event, training intensity and pre-race experience are more critical determinants of performance than specific physical dimensions.

Similar findings were observed in a study of 25 participants competing in a seven-day mountain ultramarathon covering 350 km with approximately 11,000 metres of cumulative elevation gain and loss [16]. In this event, personal best marathon time and average training speed were the two variables most strongly associated with performance.

These observations are reinforced by a broader review of physiology and pathophysiology in ultramarathon running [17]. Across studies, previous experience expressed as personal best marathon or ultramarathon times, or the number of completed ultramarathons, consistently emerged as the strongest predictor of successful performance. Training characteristics formed the second most important category, with successful athletes typically accumulating higher weekly training volumes (in both kilometres and hours) and maintaining higher average training speeds. Other factors, such as pain tolerance, age and pacing strategy, were less predictive.

Coates et al. [18] reported similar conclusions across different ultramarathon distances. In a 160 km race, no single variable predicted finishing time, but training volume was strongly associated with completion: finishers averaged 77 km per week compared with 51 km per week for non-finishers. In the 80 km race, peak velocity was the sole predictor of performance, while in the 50 km race, performance was best explained by a combination of running fitness (VO2max and peak velocity) and training volume. It is important to note the limited sample sizes in this study, with only eight finishers in the 160 km race, 13 in the 80 km race and 21 in the 50 km race.

Taken together, these findings point to a clear pattern. Strong ultramarathon performances are built on a foundation of marathon-level fitness, combined with progressively higher training volumes to support the demands of longer distances. In practical terms, improving marathon performance and then layering additional volume on top appears far more influential than any single supplementary intervention.

To address concerns around small sample sizes and to further validate this pattern, it is useful to examine the determinants of marathon performance itself particularly given how strongly marathon ability predicts ultramarathon outcomes.

What Drives Marathon Performance

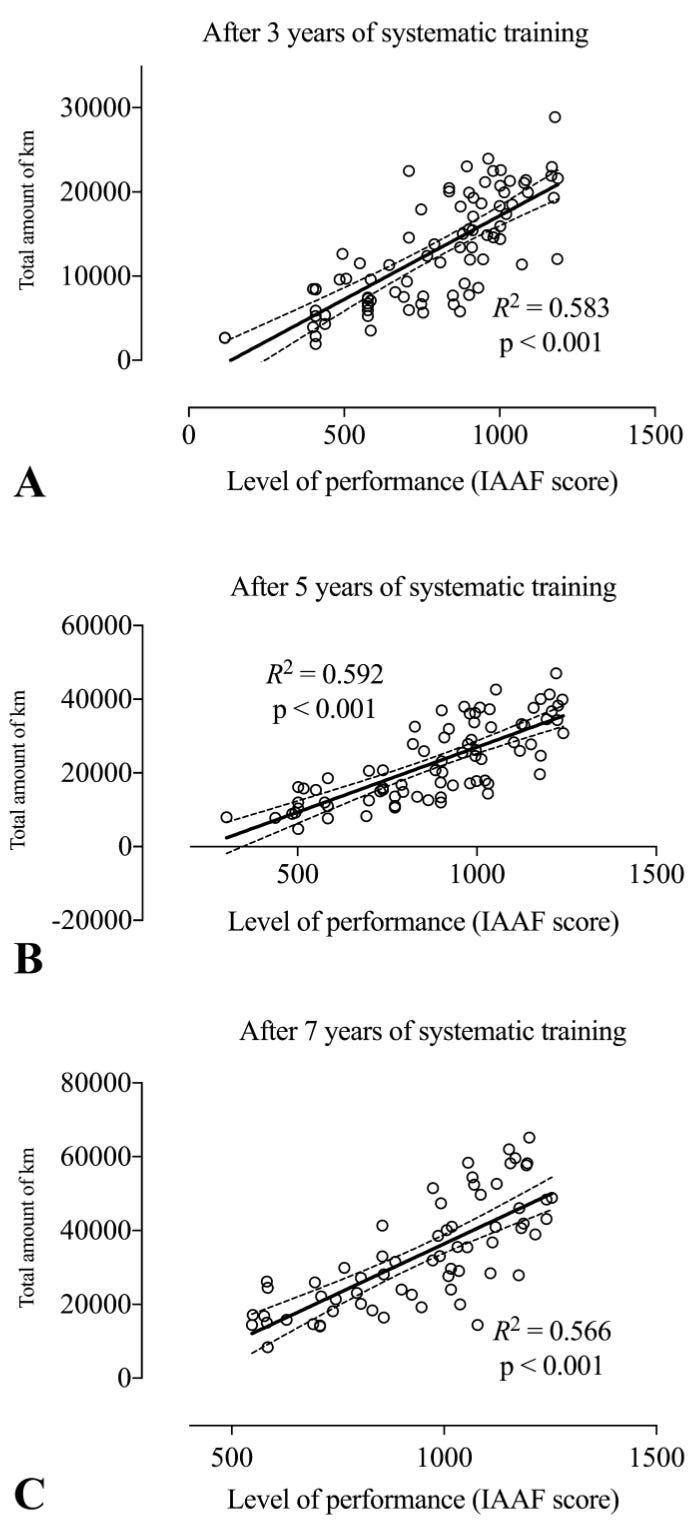

The work of Casado et al. [19] captures the central message directly in its title: “World-Class Long-Distance Running Performances Are Best Predicted by Volume of Easy Runs and Deliberate Practice of Short-Interval and Tempo Runs.” Within the study, total running distance emerged as the strongest predictor of performance, explaining up to 59% of the variability between athletes. The authors go so far as to state that there is a “fundamental need” for athletes to accumulate large training volumes, typically exceeding 100 km per week, to compete at a world-class or high national level.

Among individual training components, easy continuous runs performed at 62-82% of HRmax (zone 1-2) were the single strongest predictor of performance. These runs accounted for roughly two-thirds of total training distance in elite athletes and appear to provide the necessary cardiovascular and metabolic adaptations without the cumulative physical and psychological cost of more intense sessions.

While volume forms the foundation, the study also highlights the role of deliberate practice (defined as training activities requiring high concentration and effort) in refining performance. Tempo runs were the most influential within the deliberate practice category, increasing in importance as athletes progressed in their careers, likely due to their close resemblance to marathon race intensity. Short-interval training (200-1,000 m) also showed strong associations with performance, whereas long-interval training (1,000-2,000 m) exhibited the weakest relationship with performance variability.

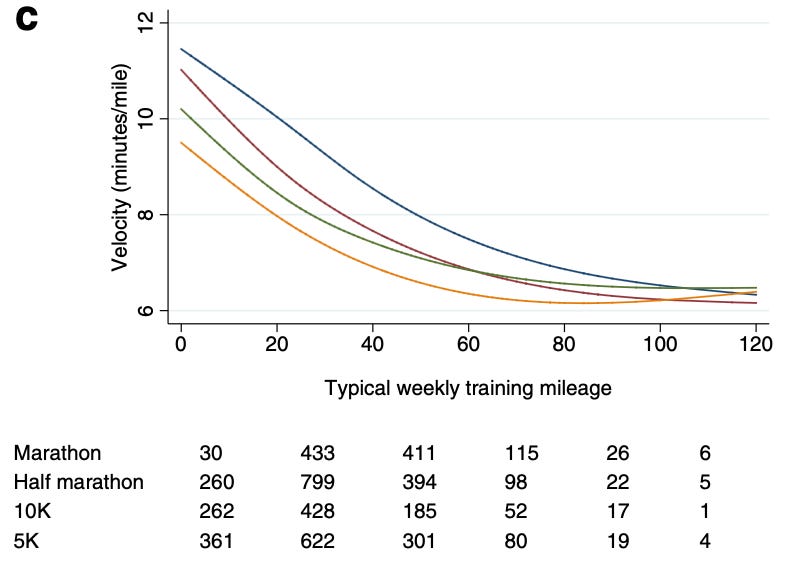

These findings are mirrored in data from 2,303 recreational runners analysed by Vickers and Vertosick [20]. Across race distances ranging from 5 km to the marathon, weekly mileage was a significant predictor of performance. Participation in tempo runs and interval training further contributed to faster race times.

Support for these conclusions also comes from a large-scale analysis using wearable data from approximately 14,000 runners, encompassing around 20 million kilometres logged across 1.6 million running activities [21]. In this study, performance was primarily predicted by the endurance index - a proxy for training impulse (TRIMP), which integrates both training volume and intensity. Increasing either running duration or running speed led to improvements in endurance index and, in turn, performance. The authors noted, however, that a seasonal TRIMP exceeding approximately 25,000 was associated with a sharp plateau in performance, which they interpreted as a potential marker of overtraining.

The second key predictor identified was the aerobic power index, a composite measure reflecting both maximal aerobic power and running economy. This index is primarily improved through higher training volumes and by increasing the amount of distance that can be covered at a given intensity, most effectively achieved through longer runs performed at a lower relative intensity.

Priorities for Performance Improvement

If you want to strength train, then by all means, strength train. There are benefits beyond performance alone. Strength training introduces variety into an otherwise repetitive training routine, provides a viable indoor alternative during poor weather and often leads to visible aesthetic changes. I have experienced all these benefits myself during periods when I included regular strength training. However, if your primary reason for adding strength training is the belief that it will take your running performance to the next level, it is worth reconsidering.

For runners averaging fewer than ten hours of running per week (roughly 75 km, including elevation) and who are not particularly injury-prone, the most effective way to improve performance is to be more consistent with your running and, in turn, run more. In practical terms, reallocating the one hour per week you might have spent on strength training towards additional running is very likely to produce greater performance gains.

For runners who are already training above this threshold, or for those who are injury-prone and struggle to tolerate further increases in running volume, cross-training can play a more meaningful role. In these cases, strength training or other forms of non-running aerobic work may provide a way to increase overall training load while managing musculoskeletal stress.

There are also specific scenarios where strength training may offer clearer benefits. For example, runners living in predominantly flat environments who are preparing for ultramarathons with substantial elevation gain and loss may benefit from targeted strength work however, these situations represent exceptions rather than the rule.

It is therefore unsurprising that Jason Koop, coach to several of the world’s top ultramarathon runners, places training volume at the base of his hierarchy of ultra marathon training needs [22], or that Steve Magness, who has coached multiple Olympic-level runners, argues that the performance of most amateur athletes is limited primarily by insufficient volume [23].

Most runners don’t need more information - they need a thinking partner.

If you are looking to balance strength training and running in 2026, coaching can help bridge that gap.

I work with athletes to make sense of where they are, identify what actually matters and move forward with confidence.

Learn more here: https://bornonthetrail.substack.com/p/coaching

This is a thoughtful and well-researched article, Niki, and I agree with its central premise: running performance is primarily driven by running, and for athletes with limited time, consistency and volume should take precedence over any supplementary work.

To play devil’s advocate, though, I don’t see this as an “either/or” question. Running volume should absolutely remain the priority, but strength training—appropriately designed, dosed, and timed—may be less about chasing the final 2–3% and more about protecting the ability to keep accumulating the stimulus that matters most: mileage.

Mileage itself, however, isn’t just a programming choice; it’s constrained by tissue tolerance, recovery capacity, and durability over months and years. In practice, many runners don’t plateau because they lack aerobic stimulus, but because their musculoskeletal system becomes the limiting factor. That’s where I think resistance training really shines.

This is in depth review of about the importance & significance of strength training and totally dissecting what is going one with strength training in the overall media.

First of all a very happy new year Niki brother.! <3

We often overestimate what we can accomplish in a day or a week and underestimate what we can accomplish in a year. Runners will try to run 100 mile weeks for a couple of months in order to get faster not knowing that this thing is all about SHOWING UP for years on end & not just a couple of weeks or months. The adaptation a person's body goes through can't be fastened like AI can summarize a book in a couple of pages. Consistency is the name of the game & not a couple of bouts of intensity workouts even though intensity plays its role in making anaerobic adaptations in our bodies. It is all about gradual build up & nailing the basics.

But 90% people don’t know it first hand as you itself know that there is a lot of fluff around running/physiology content. Everybody just wants to buy the latest pair of shoes/gadgets/clothing but what about reading books and blogs and what about sleep, nutrition, mobility/strength/conditioning exercises? What about keeping 70% of activities in Zone-1 or low intensity where the central nervous system isn’t fatigued to moderate or maximal level on daily basis.

We need to focus on what is the best we can do for our future selves irrespective of how the result pans out. 100% of shots are missed that are not taken, sho why not take the shot by keep showing up & give ourselves chance to be the best version of ourselves.

One can't get faster in just a couple of months in any sport. Even Nils Van Der Poel (Swedish Speed Skater) put up 30 hour cycling weeks to prepare for speed skating which means he was working on building a huge aerobic base to perform at his peak even though he needed a pretty good anaerobic engine as well. As it is said- Slow is smooth, smooth is fast.

Right now as I told you I am preparing for a 100 KM Stadium Run(250 laps of 400 meter). I am hoping to run it under 7 hours 30 minutes in order to get a qualifier for Team India for 100 KM World Championships 2026.

I ran a training run on 30th November(201*300M)=60,300 m in 4 hours 26 minutes. I never felt fatigue much and the aftermath of this training run wasn't much but just a couple of blood blisters. No high level fatigue felt in Central Nervous System, no quads blow up. I was pretty confident that heck yeah I can do it now as I have done simulation but after that on 23rd December I felt some knee pain and I took a couple of days off. After that I came back to running 12 KM for 2 days then 15 KM for 1 day, 18 KM for 1 day, 21 KM for 1 day & now for the last 2 days I have been running 28 KM(all of this in a single run). Today I averaged 5:25 pace per KM for 28 KM. And I am targeting 4:30 pace per KM for 100 KM on 24th January.

I on personal level do minimum amount of strength training.

I still believe I can do it but can't bring my ego to training as I would want the results right now and in order to achieve that I will increase both the volume & intensity for just a couple of weeks which can hamper. I have said to myself that it is better to be healthy at the starting line then burying my body into the ground. I want results, I want a spot in Team India but what's the point of spot when I will be injured. So, just keeping things into perspective is what I am doing right now. I am in it for the FUN and for the long haul & can't SELL MYSELF SHORT for this particular race.