Can Run Clubs Make You a Better Runner?

A deep dive into studies on run clubs, motivation and training quality, showing how group runs can help or hinder long-term success.

"Run Clubs are the new Night Clubs", claims Strava's 2024 report [1], citing a 59% global increase in running club participation. The data suggests a shift in social dynamics, with users being four times more likely to want to meet people through working out than at a bar. 58% of survey respondents said they made new friends via fitness groups, which translated to a 40% average increase in activity length (runs, rides, hikes) with more than 10 people versus when alone. This trend reflects a need for connection, particularly in a post-pandemic world.

Research on endurance athletes during COVID-19 lockdowns [2] revealed that runners were especially susceptible to the negative effects of social isolation, experiencing lower motivation, higher stress, worse sleep quality, increased consumption of alcohol, and a measurable loss of fitness. It is therefore unsurprising that runners have since flocked to run clubs to regain that sense of community.

But for the performance-focused athlete, this raises a critical question. While the social benefits are clear, can running in groups actually make you faster? On the surface, the logic holds: a supportive community could provide the motivation to run more, harder, and for longer. However, the link between social running and tangible performance gains is more complex than it first appears. This article delves into the science to understand and quantify the positive effects of social running, along with outlining some possible negatives.

Are Club Runners Faster?

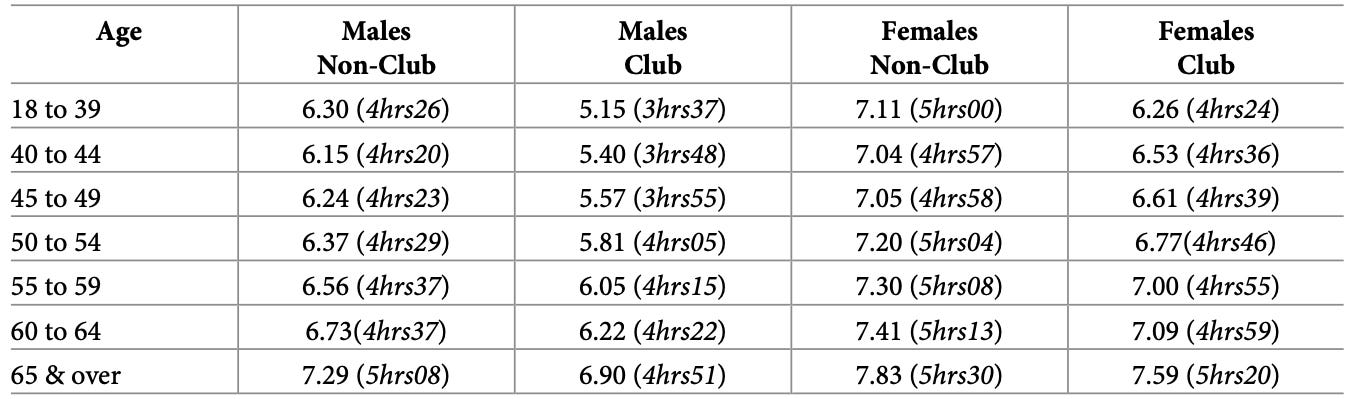

At first glance, large-scale data appears to confirm the hypothesis. A 2024 analysis [3] of the London Marathon from 2018-2023 found a strong association between running club membership and performance. Across all age and gender categories, club-affiliated runners had significantly faster finishing times, sometimes by as much as 40 minutes, than their non-affiliated counterparts.

However, this correlation doesn't automatically imply causation. As the study's authors note, club membership is a holistic variable that captures numerous tangible and intangible benefits. The act of joining a club does not, in itself, make you faster. This raises the question of whether the club setting creates faster runners, or whether faster, more dedicated runners simply self-select into clubs?

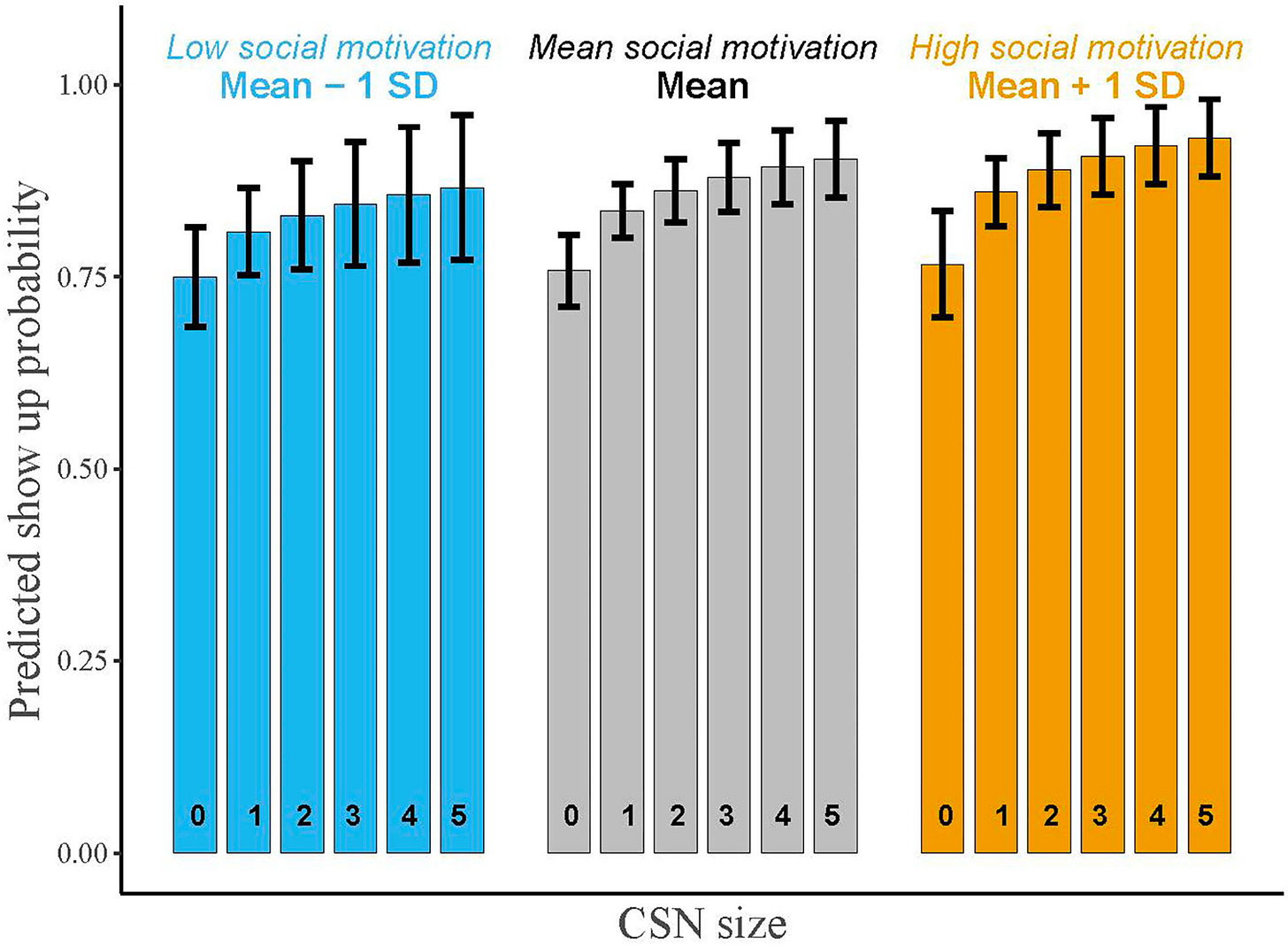

A study of over 800 runners in The Netherlands [4] adds another layer to this question. It found that athletes in large, close-knit running groups tend to run more frequently. Additionally, the effect was more significant when running with partners of a higher competence level compared to those of a lower one. This finding suggests that the performance benefits may not stem from participation alone, but may also depend on characteristics of the group members themselves.

To understand the true impact, we need to move beyond participation metrics and examine the direct physiological and psychological effects of group running.

Does Running Together Make You Faster?

While participation data hints at better outcomes, the question is whether running with others triggers a direct physiological performance improvement. Does our body actually work harder or more efficiently in a group setting? The scientific evidence presents a compelling and somewhat unexpected picture.

The Effect on Self-Paced Efforts

One of the first questions is whether the mere presence of another runner alters our natural, self-selected pace. A 2014 dissertation by Andrew J. Carnes [5] explored this by having participants complete a duration-bound run under three conditions: alone, with a familiar peer, and with an unfamiliar peer, all matched for sex and fitness.

The results showed that compared to running alone, the presence of another person, whether familiar or not, did not cause runners to alter their speed, duration, or total distance covered. In essence, for a standard, self-paced run, having a partner didn't physically change the result. However, the author noted that this finding might not hold true for structured, high-intensity sessions with specific pace or distance goals, where group dynamics could be more influential.

Group Dynamics in High-Intensity Training

Following that logic, several studies have examined the effect of group dynamics on high-intensity interval training (HIIT). In one experiment, Martin et al. [6] had 53 amateur athletes perform 30-second interval sessions over four weeks. Participants trained either alone, in an "aggregate" setting (with others nearby but no interaction), or in a "true group" with common goals and identity. While all participants improved from the training, the "true group" intervention did not produce greater physiological gains than the other two conditions.

This finding has been echoed in other studies. One trial [7] had 17 runners from the same club perform 8x400m uphill repetitions at a 16-18 on the RPE scale, once alone and once in a group. The results showed no significant difference in average interval speed or perceived exertion (RPE) between the sessions.

However, a 2019 study on elite middle-distance runners [8] provides an interesting nuance. When performing 4x500m repetitions, athletes showed no difference in overall performance time between individual and collective sessions; however, the sessions performed as a group resulted in lower post-repetition blood lactate concentrations. Lower lactate for the same speed indicates that the degree of metabolic strain was lower, meaning the effort was physiologically less costly. The authors speculated that if the athletes hadn't been given target times, they might have run faster in the group session for the same perceived effort.

A Surprising Yet Confusing Picture

Across workouts and athlete abilities, studies consistently show little to no direct improvement in speed or duration from group training. The one promising finding is the potential for reduced metabolic strain, suggesting an effort may feel easier in a group even when performance is identical.

This general lack of a clear physiological 'win' deepens the puzzle presented by the marathon data. If running in a group doesn't reliably make our bodies physically faster during a given session, why do club runners, on average, perform so much better? The answer may not lie in our muscles and lungs, but in our minds.

If Not Faster, Maybe Happier?

The lack of direct physiological gains leads us to a logical next question: perhaps the true benefit of group running is psychological rather than physical. The same studies that measured pace and lactate also explored metrics like motivation, enjoyment, and the Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE). Here, a much clearer picture begins to emerge.

The Right Group vs a Crowd

A key finding across multiple studies is that the quality of the group interaction is paramount. The study by Martin et al. [6], which had 53 amateur athletes perform 30-second interval sessions alone or in different group settings, found that participants training with others were more motivated than those running solo. Interestingly, there was little difference in motivation between the unstructured "aggregate" group and the formal "true group." They hypothesised that this is because the intervention used to create a strong unity within the “true group” of new people didn’t provide the desired results, so the conditions of the “true group” and the aggregate group ended up being similar.

However, the study by Carnes and Mahoney [7], which had 17 runners perform 8x400m uphill repetitions, adds an additional layer of detail. While they found no overall difference in RPE or enjoyment between group and individual sessions, participants who felt supported and united over a shared goal reported significantly lower RPE values and higher enjoyment.

These findings suggest that while simply being around other runners can boost motivation, the deeper psychological benefits, like making an effort feel easier and more enjoyable, depend on a genuine sense of cohesion and shared purpose within the group.

Making Hard Efforts Feel Easier

The most compelling evidence for a psychological advantage comes from the high-intensity scenarios. The 2019 study [8] on elite middle-distance runners found that during the 500-meter repeats, the group setting resulted in a lower RPE and a more positive mood, even though the running intensity was identical to the solo sessions.

This psychological data aligns perfectly with the physiological finding of lower blood lactate mentioned earlier. While the lower lactate levels may also be due to the drafting effect in the group setting, they theorised that the shared responsibility of pacing may have also played a part in reducing the psychological and physiological effects of the session. Therefore, the combination of improved mood and reduced perceived exertion can be a powerful tool for tackling demanding workouts.

When the Group Effect Fades

While the benefits during intense efforts are clear, the group effect seems to diminish in lower-stakes situations. The dissertation by Andrew J. Carnes [5], which found no physiological difference in self-paced runs, also found no difference in RPE or session enjoyment when participants ran alone versus with a peer. The authors theorised that in a low-pressure, self-paced training context, peer presence simply wasn't a strong enough stimulus to change how recreational runners ran or felt.

An Overall Positive...with a Problem

The evidence strongly suggests that while running in a group may not directly make you faster in a single session, exercising with the right group can improve key psychological metrics.

This leads to an indirect performance benefit where higher motivation, increased enjoyment, and a lower perception of effort can improve your adherence to a training plan and increase your willingness to tackle challenging workouts. Over time, this consistency is what ultimately makes you a faster, stronger runner.

However, the dynamics of group running aren't universally positive. There is one significant pitfall that, if ignored, can derail progress and potentially outweigh all of these benefits.

The Pitfall of Standardised Training

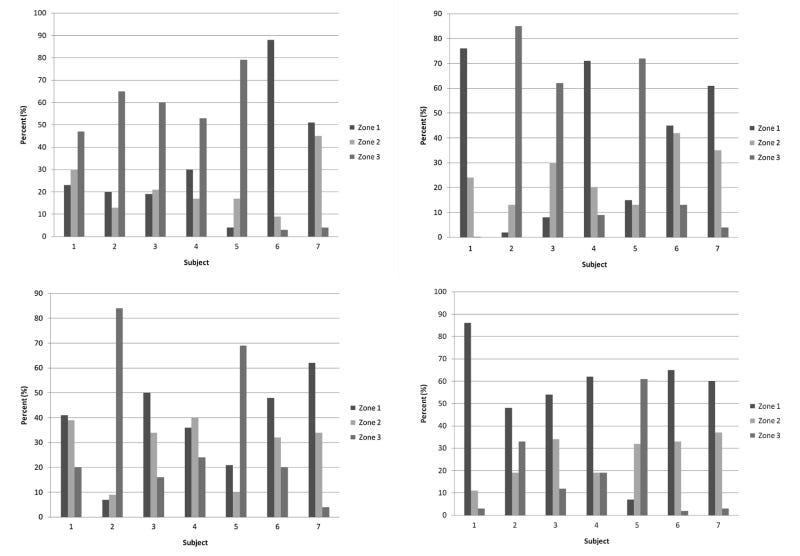

The primary challenge with group training is the inherent conflict between a standardised group workout and the unique physiological needs of each runner. Even when a group performs the "same" session, individual responses can vary dramatically. Research into adolescent cross-country teams highlights two opposite, but equally detrimental, risks.

A study conducted by Loprinzi et al. [9] observed that group settings can encourage social loafing, a psychological phenomenon where individuals exert less effort in a group than when working alone. The theory is that when individual contribution is less visible and accountability is diffused, the motivation to give 100% can drop.

In the context of a running workout, this meant that even though athletes were instructed to run at their threshold, some subconsciously held back. Without the pressure of individual accountability, their effort level drifted away from the session's intended goal, resulting in a less effective training stimulus.

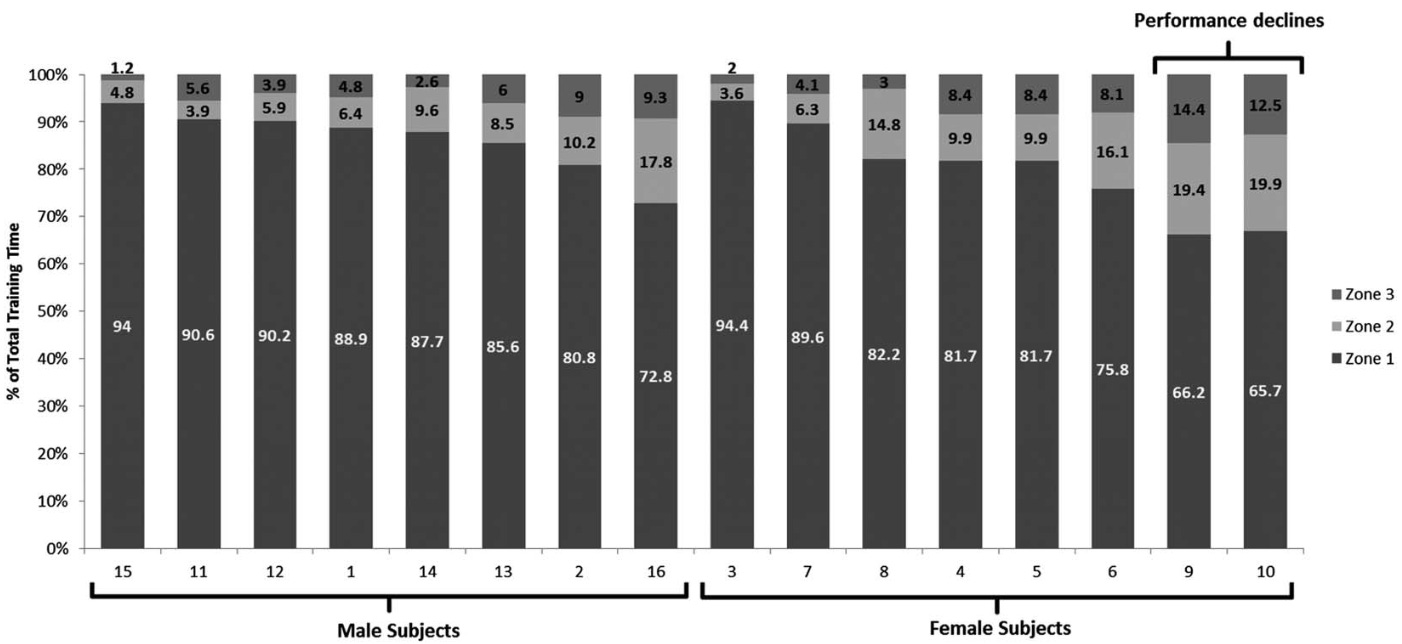

The opposite risk is perhaps even more damaging for performance-focused athletes: pushing too hard to keep up with faster teammates. Another study [10] on a youth running team found that while all athletes were given identical workouts, two runners experienced a performance decline over the study period.

Analysis revealed these athletes were spending far too little time in the prescribed easy effort zones. Instead of the targeted 80% of time in Zone 1 (easy/recovery), they were only managing around 66%, pushing into Zones 2 and 3 to stay with the group. This over-exertion on days meant for recovery likely led to fatigue accumulation, inefficiency, and early symptoms of overtraining.

These studies reveal the flaws of one-size-fits-all group training. The social dynamic can easily cause you to deviate from the intended purpose of your workout, either by holding back or, more commonly, by pushing too hard.

While the motivation and enjoyment from running with others are valuable, they should not compromise the physiological goal of a session. If an easy recovery run is on your plan, it may be smarter to run it alone than to turn it into a moderately hard effort with a faster friend. Likewise, a high-intensity session requires pacing discipline that may be best achieved alone or with a partner of matched ability. For the performance-oriented athlete, knowing when to prioritise the workout's purpose over the social experience is an important skill, especially during key training periods.

A Tool in the Toolbox

The rise of social running is undeniably positive. Run clubs and group workouts provide powerful motivation, increase enjoyment, and foster a sense of community that can get anyone out the door. While the science shows that a group setting may not provide a direct physiological boost in a single session, its power lies in the indirect benefit of greater consistency. Higher motivation and enjoyment are the foundations of long-term training adherence, which is ultimately what drives performance.

However, as we've seen, this social benefit comes with a significant risk. The danger of group running is compromising the physiological purpose of your workout. A session can easily become too hard or too easy when trying to match the pace of others, turning a targeted training stimulus into an untargeted session that misses the intended goal. At best, this is an inefficient use of your time and, at worst, it can lead to excessive fatigue and a performance decline due to a lack of proper recovery.

Ultimately, group running is a tool in your training toolbox. Like any tool, its effectiveness depends on how you use it. When leveraged wisely, for motivation on an easy day or camaraderie during a long run, it can be incredibly beneficial. But when used improperly, pushing too hard on a recovery day or holding back during a key workout, it can be detrimental to your goals. The art lies in knowing when to prioritise the social connection and when to prioritise the solitary focus required for performance.

Now, I turn the question over to you. Do you prefer to run alone or with others? What has been your experience with run clubs or training partners? If you sought out a running group, what was your main reason for doing so?

I’m looking forward to reading your thoughts and experiences in the comments below!

I swear Niki you’re gonna end up with a PhD in either exercise physiology or sports psychology … or both!

Great post. The morale boost is huge for me when running with others but I almost always run out of my desired zone (and almost always that means I run faster than feels comfortable and faster than I’m “supposed to”. Still, I’m left feeling so positive. It was cool to have you unpack the research behind this.

I like the idea of being part of a club, am a member with merch for my community's club to support events and whatnot, but never show up to group runs. I've found I deeply need the time I run to be alone, without thinking of others (although a few friends are an exception to this!).